Skinner Street United Reformed Church has been a place of worship on this site for nearly two-and-a-half centuries and is listed Grade II* by Historic England (the second highest protection status for heritage buildings) and is the last remaining 18th-century church building in Poole.

The Royal Commission on Historical Monuments in England (it later merged with English Heritage) remarked that ‘the exterior remains one of the most interesting 18th-century nonconformist chapels in England’.

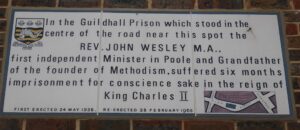

But Skinner Street’s story begins more than a century before the construction of the present church in 1777 – and not actually in Skinner Street – when in 1662 John Wesley became the first minister of a dissenting – or nonconformist – congregation in Poole. His grandson John Wesley would become the founder of Methodism.

Open Image

After studying at Oxford, John Wesley (1636–78) became rector at St Mary’s Church, Winterborne Whitechurch, near Blandford Forum, from 1658-1662, but became a victim of the Great Ejection, the mass expulsion of nonconformist clergy triggered by the Act of Uniformity in 1662.

This new law, imposed after the restoration of Charles II, required that all Church of England clergy accept without question ‘all and everything contained and prescribed’ in the revised Book of Common Prayer, published in 1662 (which remains the official prayer book of the Church of England to this day). More than 2,000 ministers in England lost their benefice after refusing to conform. Thus nonconformist ministers began to preach to those congregations outside the established church.

Open Image

According to the nonconformist historian Edmund Calamy (1671-1732) Wesley, after his removal from Winterborne Whitechurch, ‘was called by a number of serious Christians at Poole to be their pastor, in which relation he continued to the day of his death, administering all ordinances to them as opportunity offered’. It is not clear where precisely in Poole these early nonconformists met, probably in a purpose-built meeting house in Hill Street, or perhaps elsewhere in discreet premises or private dwellings.

The historian J Keith Cheetham in his book On The Trail of John Wesley describes the area around Dorchester as being ‘very Protestant’ in the mid 1600s ‘with strong leanings towards nonconformity’. Bartholomew Wesley, Wesley’s father and the great-grandfather of the founder of Methodism, was also ejected from his parish at Charmouth, west Dorset. Many nonconformist clergy at this time found themselves imprisoned for illegal preaching, including father and son Bartholomew and John. In fact Wesley Jr was jailed no fewer than four times, once in Poole for six months, once in Dorchester for three months, and twice more for shorter spells.

Open Document

After Wesley’s death in 1678 the Poole nonconformists continued to flourish, so much so that a purpose-built meeting house was erected in the forbiddingly named Hell Street (now Hill Street) in 1705. This was extended just 14 years later to meet the needs of the growing congregation. According to John Sydenham’s forensic examination of Poole, The History of the Town and County of Poole, published in 1839, this enlarged building was now ‘fifty feet square with a double roof supported by four pillars in the centre’.

Sydenham explains that it was during Samuel Phillipps’ ministry that differences of religious doctrine began to emerge among the Hell Street congregation, between supporters of Phillipps who believed in the doctrine of the Trinity (Trinitarians) and those who rejected this doctrine (Unitarians).

Get in Touch

Sydenham writes: ‘The dissenting congregations generally were much agitated with the question of the Trinity … the diversity of sentiment prevailed to such a degree that a division of the society took place in … 1760. The pastor [Phillipps], who adhered to his Trinitarian faith, maintained his doctrine in a manner displeasing to a majority of his hearers and, after much indecorous altercation, he was at length locked out of his pulpit and his adherents followed him and founded the independent congregation still assembling in Skinner Street.’

The Skinner Street congregation soon had their own building in Lag Lane (today’s Lagland Street) and within two decades, the church we see today was constructed at a cost of £1,400. This was 1777, one year after America declared independence, 12 years before heads would roll in the French Revolution, and three decades before a rough stretch of heathland to the east of Poole would start life as Bournemouth.

Open Document

Our church has another claim to fame: in 1787 the clergyman-physician Dr John Clinch (1749-1819) founded a Sunday School at the Skinner Street chapel, one of the first in England, following the model set by Robert Raikes, recognised as the father of Sunday Schools, and a man Clinch came to know and respect while he was training in Gloucester.

Clinch was born in Gloucestershire and studied to be a doctor; alongside him was his schoolfriend Edward Jenner, who later carved a place in medical history with his discovery of the smallpox vaccine. It was the world’s first vaccine and a medical breakthrough that Clinch would later introduce to North America.

Clinch had sailed to Newfoundland in the 1780s at the urging of George Kemp, a Poole merchant and deacon at Skinner Street, who wanted him to provide medical care for Poole fishermen in the colony. The young doctor was a devout Christian and the people of Trinity, a fishing community largely owned by Poole merchants like Kemp, petitioned for him to become their rector. So Clinch returned to England to begin an intensive course of study and training for the priesthood.

Open Image

He lived during this period in Hamworthy, separated from Poole as it is now by a harbour channel, but at that time with no church and no bridge. Its residents, many of them poor families, were effectively cut off from worship. While there, Clinch gathered together a number of children who had no opportunity for receiving any education and taught them the rudiments of reading and writing and a knowledge of the Christian Gospel.

Clinch decided it was time for 16 of these boys and girls to attend public worship. Accordingly, one Sunday morning he ferried them over the harbour to the town quay and marched the ‘boat children’ to the parish church of St James. The church wardens said they were unable to accept them. The children were unkempt and the wardens insisted they were already responsible for a large number of poor children in the Poole parish. Besides, Hamworthy was then in the parish of Sturminster Marshall, they argued. So Clinch took them along to the Skinner Street Independent Church where they were warmly welcomed and thus the Skinner Street Sunday School was founded.

Open Image

The children’s pews, found in the gallery today, are a very clear reminder of the days when the only place to learn reading and writing was on Sundays.

Within two years, Sunday schools had also been formed at St James’s Church and at the Unitarian Church – from which the Skinner Street congregation had split a generation earlier.

Open Image

The present church is little changed from the original 1777 design, but various alterations and improvements have been made over the ensuing two-and-a-half centuries to accommodate the changing requirements of the congregation. Most notable of these was the construction of the impressive galleries in 1823 which increased the seating capacity of the church to 1,200; our congregation today falls a little short of that number! In 1833 the distinctive neoclassical portico enhanced the front elevation of the church.

Also in the early 1830s an infant school was built which doubled as a place of weekday worship with a capacity of 300. Sydenham writes: ‘The congregation procured a master and mistress for the infant school … [which] is open to the families of every denomination, as it would be extravagance and folly to think of converting an institution [for] the benefit of young children into a sectarian society by either attempting to proselytise the little innocents or to exclude them from a share of its advantages.’

Open Image

Once the church was erected in 1777, the Lag Lane building, which had been used since the move to Skinner Street in 1760, served as a day school and Sunday School for the next century or so. By 1877 the number of children at the British Boy’s Infant School had increased so much that the building on what was now Lagland Street was demolished and a new one constructed.

Open Image

The lower floor of the British School, which doubled as a Sunday School and boys’ infant school. It opened as a Lancastrian School in 1812. But the teaching methods espoused by Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), which involved harsh discipline, came to be discredited.

The movement ejected Lancaster and renamed itself the British and Foreign Schools Society, thus the name of the school in Lagland Street changed in 1846 to the British School.

Photograph: Poole Museum

Open Image

The upper room of the British School configured for Sunday School classes.

The image, which is dated 1877, the year of the building’s demolition, appears to show furniture arranged for at least a dozen classes.

Photograph: Poole Museum

Open Image

So, how did the quayside streets, alleyways and cries of Poole look and sound two centuries ago? And what were the neighbours like? Well, this photograph – and the story behind it – allow us a fascinating insight. The image shows the homes of Skinner Street as seen from the churchyard (now car park) of Poole Congregational Church, as it was then known.

No 1 (with the bow window) was the home of Thomas and Hannah Gosse. Philip Henry Gosse (1810-1888) was the second of their four children and lived in Skinner Street from the age to two to 17. He went on to become a celebrated naturalist, zoologist and marine biologist. He is credited with not only inventing the seawater aquarium, but the word ‘aquarium’ itself (they had previously been known as ‘marine vivariums’) and his illustrations of marine life are meticulous and exquisite. It is pleasing to think that Gosse’s childhood spent rockpooling and mudlarking in Poole Harbour and the quayside so close to his home led to such great things.

Open ImageWe know from the later writings of Gosse’s son Edmund (1849-1928) that his father did attend church in Skinner Street and was a member of the choir, though (whisper it quietly) he later confessed to finding the meetings ‘dreary’. Henry’s older brother, William, played the violin at the church and their two younger siblings, Elizabeth and Thomas, were baptised there.

After his time in Poole, Gosse had spells in Newfoundland and Alabama among other places, all the while marvelling at the natural world around him, though he was dismayed at the sight of slavery in the plantations of the Deep South. Returning to England, he would join the Plymouth Brethren and his deepening evangelism distanced him from his peers in the world of science – and by some Christians – as he held fast to his creationist beliefs. Even as his contemporary Charles Darwin (they were born a year apart) was writing On the Origin of Species, Gosse’s book Omphalos was published. In it he rejected Darwin’s theories by arguing that God had created the whole fossil record as if evolution had occurred, even though it hadn’t. While Darwin had captured the zeitgeist, Gosse’s views – and his book – floundered.

The writings of his son Edmund Gosse bring Poole of the early 1800s – and particularly the area around Skinner Street – vividly to life. Edmund wrote a book – some say hatchet job – of his relationship with his father, Father and Son, which was published in 1907. Still in print today it is described as a classic of 20th-century literature and has been dramatised for television and radio.

But a few years before Father and Son, Edmund penned a more orthodox biography of his father, The Naturalist of the Seashore – The Life of Philip Henry Gosse, this time including extensive descriptions of his upbringing in Skinner Street and the daily musings of a fledgling naturalist.

Open Image

The following passage in particular jumps out of the page as it describes in vivid detail the sights and sounds of the Poole Quay in 1812; you can practically smell the tar, turpentine and rotting fish …

The borough and county of the borough of Poole, to give it its full honours, possessed in those days a population of about six thousand souls. It was a prosperous little town, whose good streets, sufficiently broad and well paved, were lined with solid and comfortable red-brick houses. The upper part of the borough was clean, the sandy soil on which it was built aiding a rapid drainage after rain. The lower streets, such as the sea end of Lagland and Fish Streets, the Strand, and the lanes abutting on the Quay, were filthy enough; while the nose was certainly not regaled by the reeking odours of the Quay itself, with its stores and piles of salt cod, its ranges of barrels of train [whale] oil, its rope and tar and turpentine, and its well-stocked shambles for fresh fish, sometimes too obviously in the act of becoming stale fish. Yet, among seaport towns, its character was one of exceptional sweetness and cleanliness. And here, though the memory is one of some years’ later date, I may print my father’s impression of the Poole of his early childhood:

“The Quay, with its shipping and sailors; their songs, and cries of ‘Heave with a will, yoho’; the busy merchants bustling to and fro; fishermen and boatmen and hoymen in their sou’westers, guernsey frocks, and loose trousers; countrymen, young bumpkins in smocks, seeking to be shipped as ‘youngsters’ for Newfoundland; rows of casks redolent of train oil; Dobell, the gauger, moving among them, rod in hand; customs officers and tide-waiters taking notes; piles of salt fish loading; packages of dry goods being shipped; coal cargoes discharging; dogs in scores; idle boys larking about or mounting the rigging – among them Bill Goodwin displaying his agility and hardihood on the very truck of some tall brig – all this makes a lively picture in my memory, while the church bells, a full peal of eight, are ringing merrily. The Poole men gloried somewhat in this peal; and one of the low inns frequented by sailors, in one of the lanes opening on the Quay, had for its sign the Eight Bells duly depicted in full.

“Owing to the immense area of mud in Poole Harbour, dry at low water, and treacherously covered at high, leaving only narrow and winding channels of water deep enough for shipping to traverse, skilled pilots were indispensable for every vessel arriving or sailing. From our upper windows in Skinner Street, we could see the vessels pursuing their course along Main Channel, now approaching Lilliput, then turning and apparently coasting under the sand-banks of North Haven. Pilots, fishermen, boatmen of various grades, a loose-trousered, guernsey-frocked sou’westered race, were always lounging about the Quay.”